Sign Up For Our Newsletter

National Charter School Law Rankings & ScoreCard — 2024

The simple and original principle of charter schooling is that charter schools should receive enhanced operational autonomy in exchange for being held strictly accountable for the outcomes they promise to achieve. When charter school laws honor this principle, innovative, academically excellent charter schools flourish. In turn, schools that fail to produce strong outcomes close.

Since the first charter schools were established in the 1990s, the movement has spread to every corner of the country, with concentrated growth in the nation’s largest urban centers. Over time, demand for charters has skyrocketed, despite setbacks deriving from weak charter school policies, overregulation, and false perceptions of charter schools promulgated by opponents of school choice.

One of the reasons parents and students seek charters is because, when they work, they offer options that are distinct from those found in most traditional school districts. The innovations that charters are best known for are extended school days and years and, in some places, one-to-one tutoring. But charters innovate in many other ways as well: from developing unique approaches to teacher training to pioneering tools for personalized learning, many innovations that are now accepted as common were born in the charter sector.

Charter schools are popular and innovative. They are also effective. But charter school success depends on the policy environments in which charter schools operate. Some state laws and regulations encourage diversity and innovation in the charter sector by providing multiple authorizers to support charter schools and allowing charters real operational autonomy. As Michael Q. McShane has pointed out, where diversity exists, charter schools have the opportunity to innovate.

Too many states, however, hamper charter schools with weak laws and needless regulations. These make it difficult to distinguish charters from their district counterparts.

Weak charter school laws have proven that when we apply the same old rules to district and charter schools, we get more of the same. Overregulation and underfunding force charters to behave as district schools by another name. Wouldn’t it make more sense to allow charters the room to innovate and succeed so that they could, in turn, help district schools subvert the status quo?

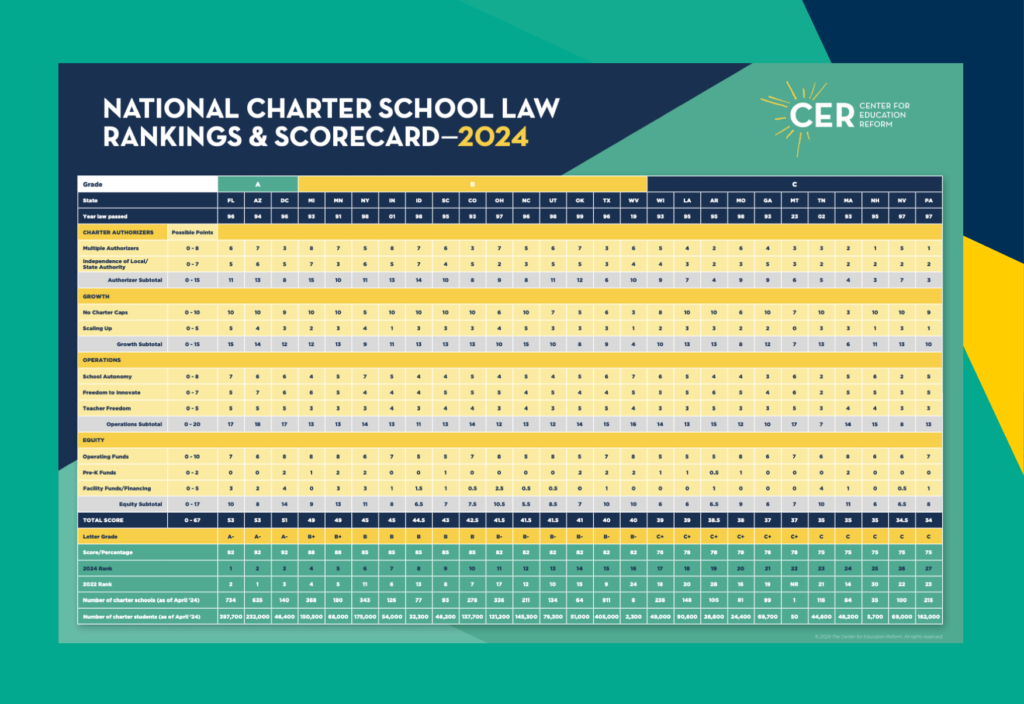

Since 1996 CER has researched, analyzed and ranked state charter school laws in an attempt to demonstrate how weak charter school laws create weak charter schools. These findings consider not only the content of each law, but also how the law impacts charter schools on the ground: How robust is the charter sector in each state? How diverse are the schools? To what extent do burdensome regulations prevent charters from doing anything meaningfully different?

Before you can have charter schools, you must have a state charter school law. Forty-six states and the District of Columbia have enacted charter school laws, with Montana being the latest in May 2023. The four states that do not have charter school laws are Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota and Vermont.

As is the case with most education laws, charter schools are born at the state level. Typically a group of concerned lawmakers drafts a bill that allows the creation of any number of charter schools throughout a state. The content of the charter law plays a large role in the relative success or failure of the charter schools that open within that state. CER has identified a number of factors that can work together to create an environment that promotes the growth and expansion of charter schools. Some of them are identified below.

- Number of Schools & Applications: The best charter laws do not limit the number of charter schools that can operate throughout the state. They also do not limit the number of students that can attend charter schools. Poorly written laws set restrictions on the types of charter schools allowed to operate (new starts, conversions, online schools), hindering parents’ ability to choose among numerous public schools. Strong charter school law allows many different types of groups to apply to open and start charter schools.

- Multiple Charter Authorizers: States that permit a number of entities to authorize charter schools, or provide applicants with a binding appeals process, encourage more activity than those that vest authorizing power in a single entity, particularly if that entity is the local school board. The goal is to give parents the most options possible, and having multiple authorizers helps reach this goal. Additionally, it is important that the authorizing entities have independent power from one another to prevent creating multiple authorizers “in name only.” For more information on why multiple authorizers are important, please see our Multiple Authorizers Primer.

- Waivers & Legal Autonomy: A good charter law is one that automatically exempts charter schools from most of the school district’s laws and regulations. Of course no charter school is exempt from the most fundamental laws concerning civil rights. These waivers allow charter schools to innovate in ways that traditional public schools cannot.

- Full Funding & Fiscal Autonomy: A charter school needs to have control of its own finances to run efficiently. The charter school’s operators know the best way to spend funds, and charter law should reflect this need. Similarly, charter schools, as public schools, are entitled to receive the same amount of funds as all other conventional public schools. Many states and districts withhold money from individual charter schools due to fees and “administrative costs,” but the best laws provide full and equal funding for all public schools.